The Iran-Contra Affair was a secret U.S. arms deal that traded missiles and other arms to free some Americans held hostage by terrorists in Lebanon, but also used funds from the arms deal to support armed conflict in Nicaragua. The controversial deal—and the ensuing political scandal—threatened to bring down the presidency of Ronald Reagan.

The Iran-Contra Affair, also known as “The Iran-Contra Scandal” and “Irangate,” may not have happened were it not for the political climate in the early 1980s.

President Ronald Reagan, who won the White House in 1980, wasn’t able to maintain the political momentum for his Republican colleagues, and the GOP was swept from the majority in both the Senate and House of Representatives in the 1982 mid-term elections.

The results would complicate the president’s agenda. During his campaign for the White House, Reagan had promised to assist anti-Communist insurgencies around the globe, but the so-called “Reagan Doctrine” faced a political hurdle following those mid-term elections.

Soon after taking control of Congress, the Democrats passed the Boland Amendment, which restricted the activities of the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) and Department of Defense (DoD) in foreign conflicts.

The amendment was specifically aimed at Nicaragua, where anti-communist Contras were battling the communist Sandinista government.

Reagan had described the Contras as “the moral equivalent of the Founding Fathers.” But much of their funding, to that point, had come via Nicaragua’s cocaine trade, hence Congress’ decision to pass the Boland Amendment.

Still, the president instructed his National Security Advisor, Robert McFarlane, to find a way to assist the drug-dealing Contras, regardless of the cost—political or otherwise.

Meanwhile, in the Middle East, where U.S. relations with many nations were strained to the breaking point, two regional powers—Iraq and Iran—were engaged in a bloody conflict.

At the same time, Iranian-backed terrorists in Hezbollah were holding hostage seven Americans (diplomats and private contractors) in Lebanon. Reagan delivered another ultimatum to his advisors: Find a way to bring those hostages home.

In 1985, McFarlane sought to do just that. He told Reagan that Iran had approached the United States about purchasing weapons for its war against neighboring Iraq.

There was, however, a U.S. trade embargo with Iran at the time, dating back to that country’s revolution and subsequent overthrow of Shah Pahlavi of Iran, during which 52 American hostages were held for 444 days in a diplomatic standoff known as the Iran Hostage Crisis.

Although several members of Reagan’s administration opposed it—including Secretary of State George Schultz and Secretary of Defense Caspar Weinberger—McFarlane argued that an arms deal with Iran would not only secure the release of the hostages, but help the United States improve relations with Lebanon, providing the country with an ally in a region where it desperately needed one.

And, as an aside, the arms deal would secure funds that the CIA could secretly funnel to the Contra insurgency in Nicaragua. With the backing of McFarlane and CIA Director William Casey, Reagan pushed ahead with the trade, over the objections of Weinberger and Schultz.

Lebanese newspaper Al-Shiraa first reported the arms deal between the United States and Iran in 1986, well into Reagan’s second term.

By that time, 1,500 American missiles had been sold to Iran, for $30 million. Three of the seven hostages in Lebanon were also released, although the Iran-backed terrorist group there later took three more Americans hostage.

Reagan initially denied that he had negotiated with Iran or the terrorists, only to retract the statement a week later.

Meanwhile, Attorney General Edwin Meese launched an investigation into the weapons deal, and found that some $18 million of the $30 million Iran had paid for the weapons was unaccounted for.

It was then that Lieutenant Colonel Oliver North, of the National Security Council, came forward to acknowledge that he had diverted the missing funds to the Contras in Nicaragua, who used them to acquire weapons.

North said he had done so with the full knowledge of National Security Advisor Admiral John Poindexter. He assumed Reagan was also aware of his efforts.

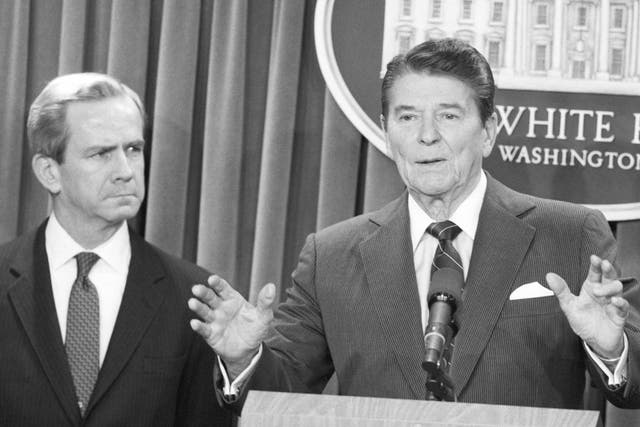

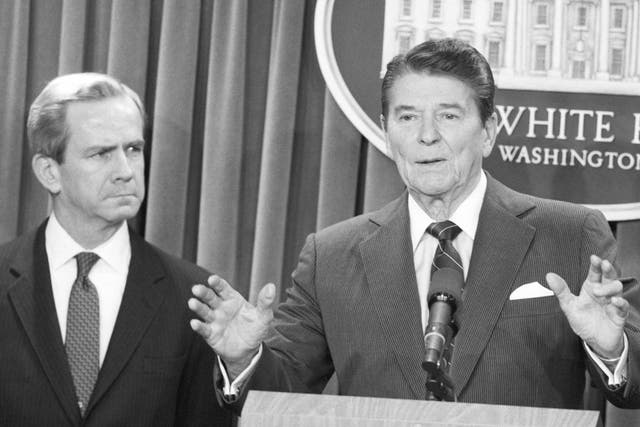

The American press hounded Reagan over the matter for the rest of his presidency. The Tower Commission (led by Texas Senator John Tower), which the president himself appointed, investigated the administration’s involvement and concluded that Reagan’s lack of oversight enabled those working under him to divert the funds to the Contras.

During a subsequent Congressional investigation, in 1987, protagonists in the scandal—including Reagan—testified before the commission in hearings that were televised nationally.

Later, Independent Counsel Lawrence Walsh launched an eight-year investigation into what by then had become known as the Iran-Contra Affair. In all, 14 people were charged, including North, Poindexter and McFarlane.

Reagan himself was never charged, and, in 1992, George H. W. Bush, Reagan’s vice president who was elected president in 1988, preemptively pardoned Weinberger.

McFarlane was charged with four counts of withholding information from Congress, a misdemeanor. He was sentenced to two years’ probation and $20,000 in fines.

North was charged with 12 counts relating to conspiracy and making false statements. Although he was convicted in his initial trial, the case was dismissed on appeal, due to a technicality, and North has since worked as a conservative author, critic, television host and head of the NRA.

Poindexter was initially indicted on seven felonies and ultimately tried on five. He was found guilty on four of the charges and sentenced to two years in prison, although his convictions were later vacated.

In addition, four CIA officers and five government contractors were also prosecuted; although all were found guilty of charges ranging from conspiracy to perjury to fraud, only one—private contractor Thomas Clines—ultimately served time in prison.

Despite the fact that Reagan had promised voters he would never negotiate with terrorists—which he or his underlings did while brokering the weapons sales with Iran—the two-term occupant of the White House left office as a popular president.

In interviews years later, Walsh, the special counsel tasked with investigating the Iran-Contra scandal, said that Reagan’s “instincts for the country’s good were right,” and implied that the president may have had difficulty remembering specifics of the scandal, due to failing health.

Reagan himself acknowledged that selling arms to Iran was a “mistake” during his testimony before Congress. However, his legacy, at least among his supporters, remains intact—and the Iran-Contra Affair has been relegated to an often-overlooked chapter in U.S. history.

The Iran-Contra Affair—1986-87. The Washington Post.

The Iran-Contra Affairs. Brown University.

The Iran-Contra Affair. PBS.org.

Iran Hostage Crisis. History.com.

Understanding the Iran-Contra Affairs: Summary of Prosecutions. Brown University.

25 Years Later: Oliver North and the Iran Contra Scandal. Time.

The Iran-contra scandal 25 years later. Salon.com.

Iran-Contra scandal tarnished credibility/But Americans forgave president after he admitted judgment errors. SFGate.

HISTORY.com works with a wide range of writers and editors to create accurate and informative content. All articles are regularly reviewed and updated by the HISTORY.com team. Articles with the “HISTORY.com Editors” byline have been written or edited by the HISTORY.com editors, including Amanda Onion, Missy Sullivan, Matt Mullen and Christian Zapata.