Christine Norstadt was a Contributing Editor for the Georgia edition of the network when/where this article originally appeared in September of 2017.

Christine Norstadt is a shareholder in the law firm of Chamberlain Hrdlicka in Atlanta where she focuses on commercial real estate transactions and litigation in Georgia and throughout the Southeast.

An easement describes the right of one person to use the land of another person for a specific purpose. Because easements affect the manner in which an owner can use her property, it is important for that owner to understand: the nature of any easement affecting her property and her rights and obligations with respect to such easement.

TYPES OF EASEMENTS

There are two main categories of easements: appurtenant easements and easements in gross.

An appurtenant easement involves at least two properties and describes the rights of one property, which may be legally referred to as the “dominant estate,” over another property, referred to as the “servient estate.” Appurtenant easements will generally “run with the land” meaning that subsequent owners of the properties affected by the easement will be benefited and burdened by it, respectively.

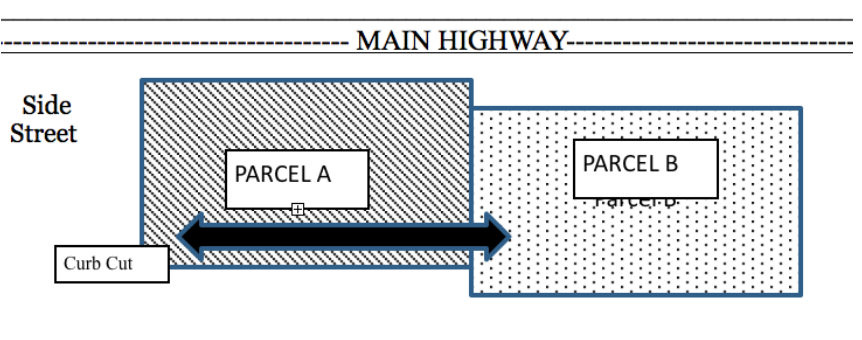

An Access Easement is an appurtenant easement. To illustrate, consider a “Parcel A” commercial property, which is located on the corner of a busy highway and side street, and “Parcel B”, a second commercial property located off the busy highway. Parcel B wants access for its customers off of both the main highway and the side street, so Parcel B may negotiate an access easement with Parcel A, under the terms of which Parcel B may use a certain portion of Parcel A’s property (depicted below with arrows) and Parcel A’s curb cut to the side street, all for the limited purpose of accessing the Parcel B property. In this scenario, Parcel A is the servient estate, and Parcel B is the dominant estate. Future owners of Parcel B will continue to have the rights over Parcel A’s property because the easement runs with the land.

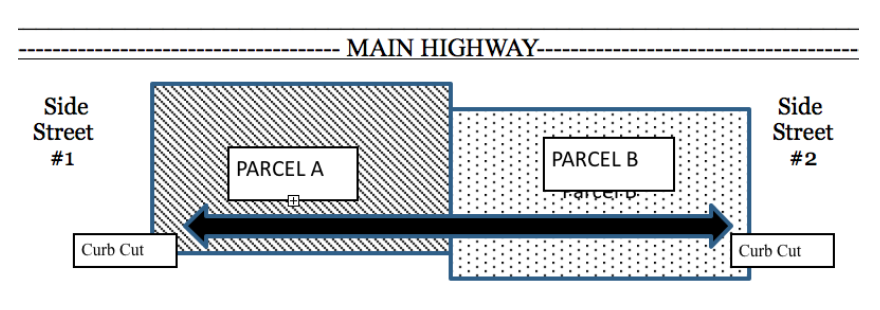

A subset of appurtenant easements are reciprocal easements, which means that each parcel has rights in the other. In a reciprocal easement agreement, a parcel is both servient as to some easement rights and dominant as to others. Returning to the example above, if we add another side street #2 adjacent to Parcel B, and Parcel A has rights to access to side street #2 by crossing over a certain portion of Parcel B, then the parties have a reciprocal easement.

While an appurtenant easement involves two or more properties, an easement in gross involves only one property and grants certain rights with regard to that property to a particular person or entity. Easements in gross also run with the land, meaning that any subsequent owner will be affected by the easement (so long as the person holding the easement rights exists). Common examples of easements in gross are right of way easements and utility easements.

CREATING AN EASEMENT

There are four ways to create an easement in Georgia:

Easements can be terminated by an express agreement of the applicable parties, and they may be legally abandoned, which requires more than just a showing of non-use of the easement.

HOW TO KNOW IF AN EASEMENT AFFECTS YOUR PROPERTY

Generally speaking, easements created by deed or law will be recorded in the public record in the form of an easement agreement, part of a deed or depicted on a recorded survey or plat of the property. An easement of any type may be apparent from a physical inspection of the property (and therefore depicted on a survey of the property, even if that survey is not recorded) or uncovered in an affidavit from the owner given at closing or a representation made in a purchase and sale agreement. Surveys are essential to understanding how easements affected property – a surveyor can plot easements on a survey of the property to provide a visual depiction of an easement for the property owner. If it is unclear if an easement affects a certain property, the surveyor can advise as to what property is described by the easement.